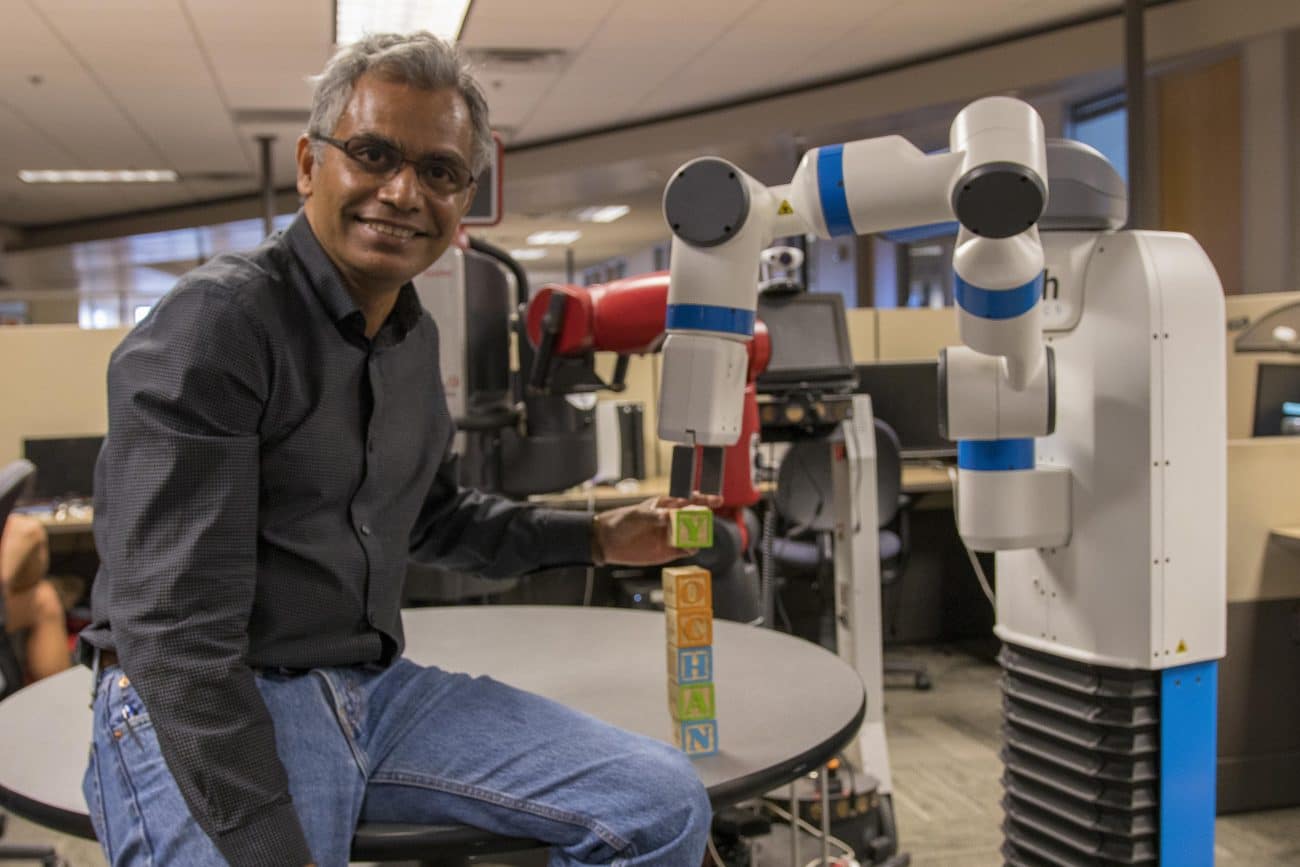

The AI field is one crowded place these days, with almost everyone donning the hat of an ‘AI expert’. In order to separate the wheat from the chaff and get some clarity, AIM got in touch with Subbarao Kambhampati, professor of AI at Arizona State University for the past 32 years, and asked him what are the things that he loves, and what gets his goat.

Kambhampati’s views on LLMs align with Meta AI chief Yann LeCun. “We both feel that there is no reason to believe that these n-gram models would be able to reason beyond what they actually do,” he said. “They are just not made and meant to do that.” He gave an example of how LLM-based chatbots are still very weak at maths problems.

This brought up Q*, the OpenAI’s leaked model that was able to solve unseen maths problems. “It has stored an entire world in itself and is just able to retrieve information, that’s all. That’s pretty much the way to use LLMs, but that is a very dumb way to learn multiplication for humans; it’s the same for AI models.”

Talking about Perplexity AI, Kambhampati says that these are the classic cases of misunderstanding what LLMs are. “They are just retrieving information and summarising it, but they still hallucinate.”

He is interested in working with LLMs where they become the guessers. Kambhampati calls this LLM modulo fashion. Similar to LeCun’s vision of autonomous machine intelligence, he also proposes a world model, with different models connected together to a larger model, for bringing out information. “LLMs can only guess, they cannot verify.”

Kambhampati’s views on LLMs do not end here. “Another thing that has changed is that instead of calling hallucinations a bug, people have started calling it a feature,” he added that most people are just getting impressed with what LLMs can do, and forget that the most important thing is to focus on accuracy, instead of just creativity, giving the example of calculators – “we want them to be perfect”.

So-called “AI Experts”

The problem that Kambhampati pointed out is that everybody thinks that they are an AI expert as the barrier to entry to become an AI ethicist, or voice for responsible AI has been lowered. “I open my LinkedIn and everyone is talking about LLMs and touting responsible AI as the focus point,” Kambhampati laughed.

“Many people have come into AI only after 2013 – and some after ChatGPT – and often end up rediscovering the things that are already discovered.”

“Biology has become the refuge for people who want to do science but do not know maths,” he laughed, giving an analogy for people who talk about responsible AI, with the knowledge of neither AI, nor ethics.

He also highlighted a conference that had 40 people discussing AI, with only one person who had actually written a research paper in their entire lives. “That’s definitely not just annoying, but worrisome,” he added that X and LinkedIn are just filled with cheerleaders of LLMs.

Recalling Mark Twain’s quote, “A classic is something that everybody wants to have read and nobody wants to read,” Kambhampati said that AI is the new classic as everybody wishes to know it, but they don’t really have the background to talk about it. “I don’t think you can get away with that just by speaking with confidence.”

He emphasised that people should learn the full spectrum of AI techniques and then use what you know is the right way to combine them. “But the problem is people do not even take an introductory course to AI, they just start working on deep learning projects.”

He also feels that education in AI is important, but only the basics are enough. “You can overdo AI education. You don’t need it, just like you don’t need to teach about electricity to everyone, but everyone uses it …using calculators is different from understanding how it works.”

Not a fan of “UN of AI”

“As much as I hate the analogy, AI is becoming like electricity. But we do not have a global electrical policy. We do not need that for AI as well,” Kambhampati said. Moreover, he is also not a fan of making one organisation narrate all the rules around AI, as it would be ineffective. “Countries should be allowed to experiment with AI for their own use cases,” highlighting that advisory is acceptable, but it should be a mix of technology and policy experts.

Being passionate about open source, he said that the rise of Llama and Mistral, and then the rise of Indic LLMs such as Kannada and Tamil, has taken the baton away from OpenAI, which is very important. He highlighted that a lot of open source smaller models are performing better than models like GPT-4 that are much bigger in size on specific tasks.

“I hate the word foundational model,” Kambhampati added. “Just because there are different modalities coming up such as videos and images, that does not mean that LLMs are starting to reason better.”

When it comes to India, Kambhampati points out that the problem with Indic LLMs is that there is more data from exam papers such as JEE and UPSC. “You can train an LLM to pass JEE, but not write something coherent in Indic languages,” he added, pointing out that this problem exists because most of the data in the Indic language is not yet digitised.

Most of the training data available today is in English, not in other languages, which Kambhampati believes is a very big problem for building large foundational models. “I said this in 2018, that data capture and digitisation would be a very big issue, but no one wants to take them up as they are unsexy.”

The Real Star of AI

“I kid around with my students that I was doing AI before it was cool,” said the self-proclaimed stand-up comic for his students.

Born in Peddapuram, Andhra Pradesh, Kambhampati went on to do his bachelor’s in electrical engineering at IIT Madras, and did his project on speech recognition that eventually got him into AI. “People would be sad that I am doing AI, when there are more exciting things like databases.”

Kambhampati admitted that his interest in LLMs started with all the hype around LLMs, as he believes that they are not just n-gram models, but can also do reasoning and planning. “But the claims that LLMs can do everything that an AI system should do, and it is complete, is not actually the case,” he explained. “They can do planning and reasoning, but not idea generation from scratch.”

Kambhampati is currently interested in working with the human-AI interaction field, which deals with AI systems that should be able to explain the decisions to humans, instead of “silly saliency regions approaches where humans try to make sense of what machines are doing.”